The growing pains of e-commerce business in Africa

High cost of logistics is making it difficult for online platforms to survive

E-Commerce has long been touted as Africa’s next high-growth market. Several reasons are cited for the optimism, among them the continent’s large, relatively young, and tech-savvy population, increasing mobile internet penetration, a fast-growing middle-class and rising disposable income.

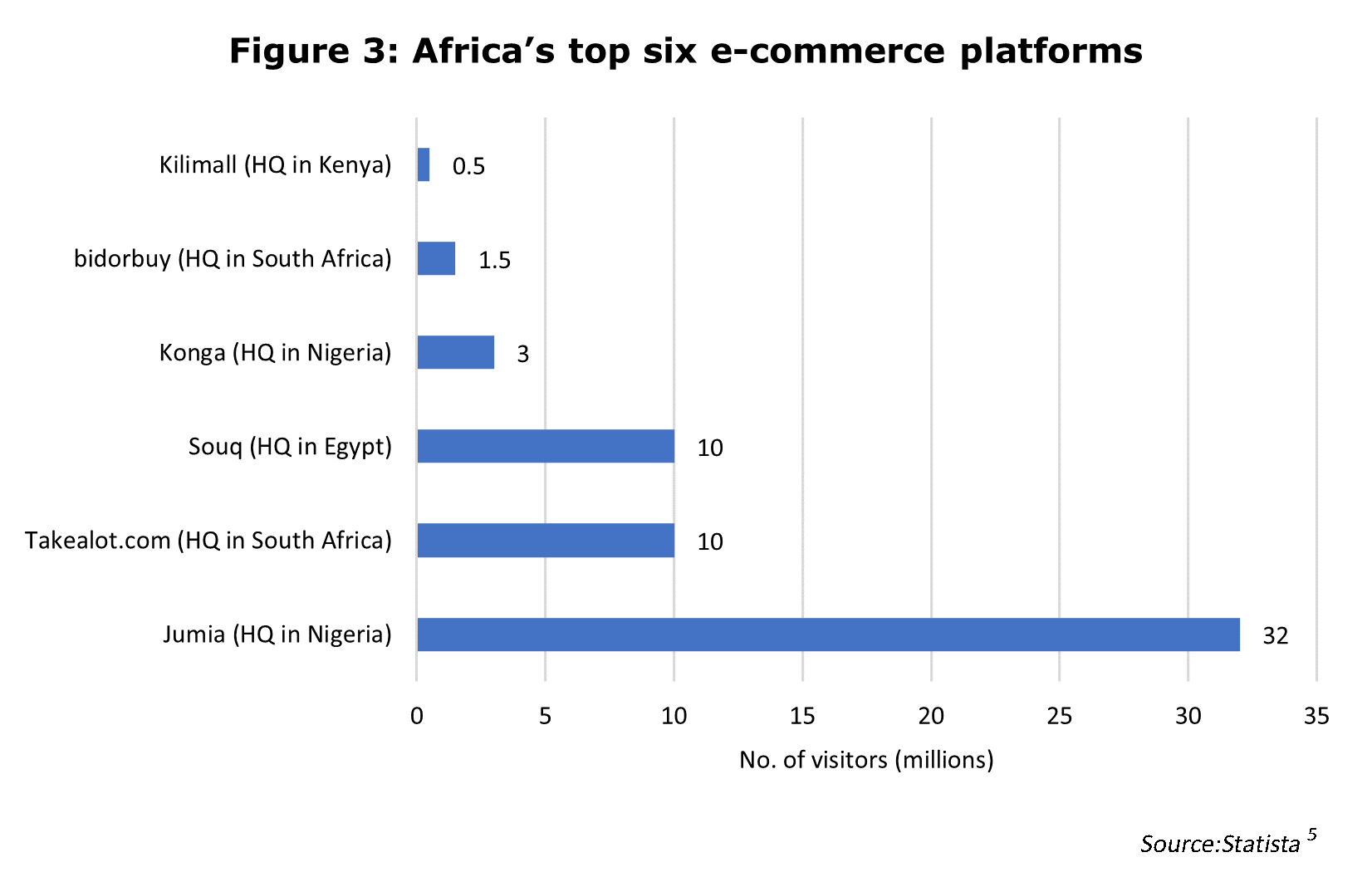

The burgeoning industry has seen the birth of homegrown e-commerce platforms such as Jumia (Nigeria), Takealot (South Africa) and Kilimall (Kenya), and the market’s potential has not gone unnoticed by bigger international players like Amazon, Alibaba, Shein and even Facebook, all of whom are positioning themselves for a piece of the e-commerce pie.

Africa, however, is a truly unique operating environment and presents its own challenges, from logistical constraints, underdeveloped infrastructure and limited payment gateways to security, access to capital and a customer trust deficit. The playing field, which is becoming increasingly crowded and putting pressure on margins and profitability, is ripe for both consolidation and disruption.

Of the continent’s e-commerce markets, South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya are among the most advanced and offer valuable lessons to potential entrants and upstarts about how to overcome Africa’s idiosyncrasies, and what happens when you don’t.

E-Commerce in Africa

Africa’s e-commerce journey began when South African platforms - Kalahari.com and Bidorbuy.com - started out in 1998 and 1999 respectively at the height of the dotcom boom. Since those early days, e-commerce on the continent has grown exponentially. There are over 264 active e-commerce sites across 23 countries in Africa.[1] South Africa alone boasts overs 105 e-commerce platforms, while Kenya and Nigeria have 60 and 58 respectively (figure 1).

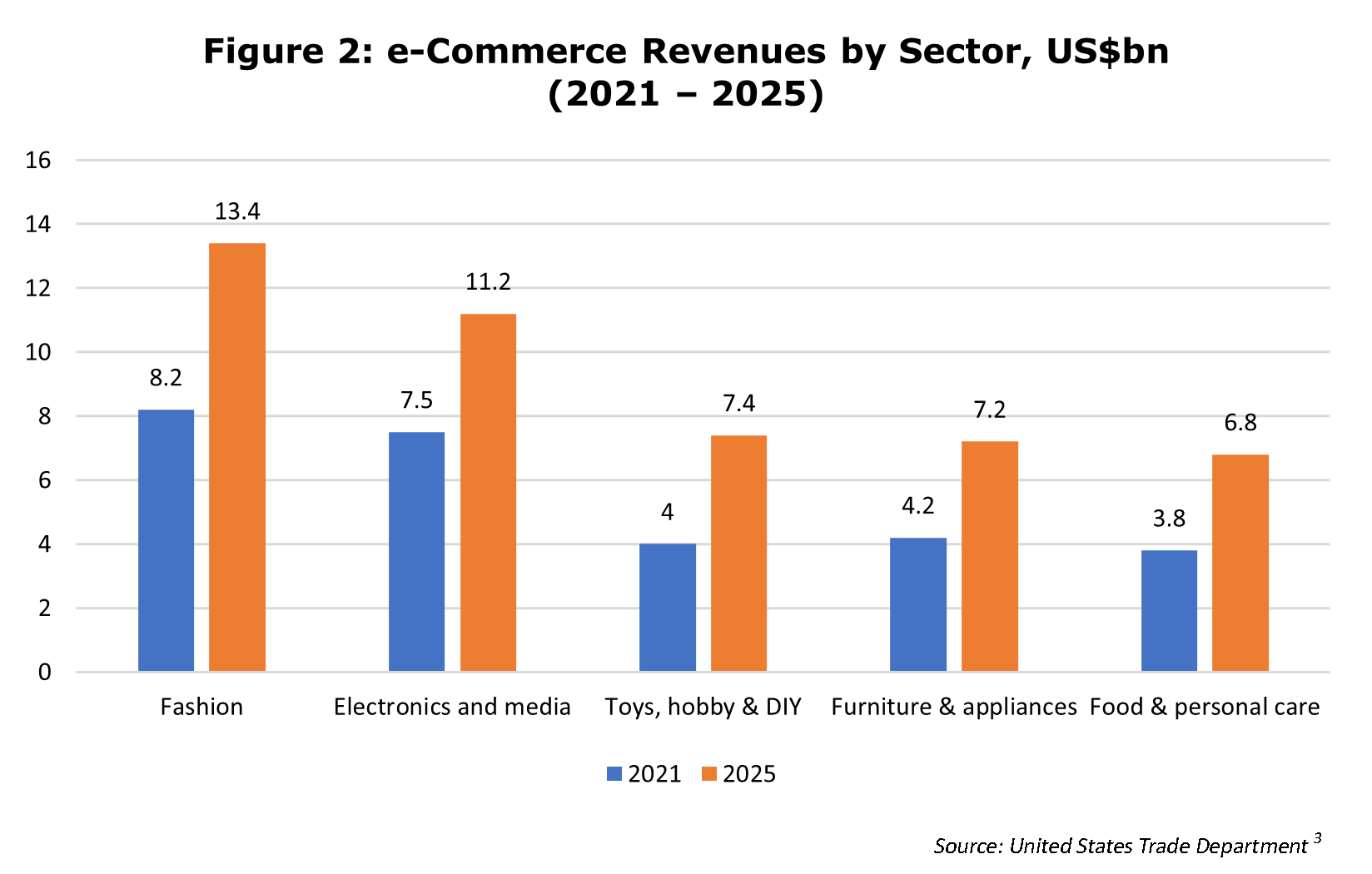

E-commerce sites have sprung up to cater to almost every consumer need - from food delivery services to everyday groceries. Data shows that in Africa fashion, electronics, and media are the biggest online spend categories. This is followed by toys, hobbies and DIY furniture. (figure 2).

Africa’s biggest e-commerce website is Nigeria-based Jumia which attracts an average of over 32 million visitors a month, followed by South Africa’s Takealot and Egypt’s Souq[4]with 10 million unique visitors per month each.

Africa’s biggest e-commerce website is Nigeria-based Jumia which attracts an average of over 32 million visitors a month, followed by South Africa’s Takealot and Egypt’s Souq[4]with 10 million unique visitors per month each.

The e-commerce penetration rate in Africa is expected to breach the half-a-billion user mark by 2025 (40%), up from just 139 million users (13%) in 2017. That represents a compounded annual growth rate of 17% (figure 4).

The e-commerce penetration rate in Africa is expected to breach the half-a-billion user mark by 2025 (40%), up from just 139 million users (13%) in 2017. That represents a compounded annual growth rate of 17% (figure 4).

Notably, most of the e-commerce traffic comes from mobile devices – more than 70%. It is expected to be almost exclusively mobile by 2040.[7]The 281 million currently active online shoppers in Africa[8]are forecast to drive revenue to US$49bn in 2023 and to US$82bn in 2027[9] (figure 5).

From a growth perspective, Africa’s e-commerce story is a compelling one. But from the profitability point of view it is still a long way from maturity. Despite the double-digit revenue advance since 2017, Africa makes up less than 1% of the US$6.3tn global e-commerce economy. While the expansion of mobile telecommunication networks, uptake of smart devices, rising disposable income and large population are big drivers of online commerce growth, they don’t tell the full story. A 2017 report by Disrupt Africa found that less than 30% of Africa’s e-commerce start-ups were profitable.[11] The lack of profitability is not limited to start-ups, however. Many of the biggest e-commerce companies on the continent have not yet turned a profit after more than a decade of trading, surviving only on capital injections from venture funders or parent companies. Nigeria’s Jumia, South Africa’s Takealot and Kenya’s Kilimall, all leaders in their respective countries, offer valuable insight into the challenges of turning an e-commerce profit in Africa.

From a growth perspective, Africa’s e-commerce story is a compelling one. But from the profitability point of view it is still a long way from maturity. Despite the double-digit revenue advance since 2017, Africa makes up less than 1% of the US$6.3tn global e-commerce economy. While the expansion of mobile telecommunication networks, uptake of smart devices, rising disposable income and large population are big drivers of online commerce growth, they don’t tell the full story. A 2017 report by Disrupt Africa found that less than 30% of Africa’s e-commerce start-ups were profitable.[11] The lack of profitability is not limited to start-ups, however. Many of the biggest e-commerce companies on the continent have not yet turned a profit after more than a decade of trading, surviving only on capital injections from venture funders or parent companies. Nigeria’s Jumia, South Africa’s Takealot and Kenya’s Kilimall, all leaders in their respective countries, offer valuable insight into the challenges of turning an e-commerce profit in Africa.

Jumia – Nigeria

Jumia, once dubbed the “Amazon of Africa”, was arguably the continent’s most celebrated start-up and the first ‘unicorn’ (a startup whose market valuation hits US$1bn). It operates across 10 African countries selling everything from electronics to homeware, fashion, and groceries. More recently, it has expanded into logistics, hotel and travel booking, food delivery and payment services.

The firm, which is headquartered in Berlin, and whose senior leadership and software developers operate from Dubai and Portugal respectively, was launched in 2012 in Nigeria as an African company with the financial backing of German venture capital firm, Rocket Internet and South African mobile telecommunications company, MTN. In 2019, Jumia listed on the New York Stock Exchange[12] raising US$196m.[13] But since the IPO, which saw the share soar threefold from its listing price ($US14.50), the stock has fallen more than 90% from its all-time high (of US$62 in February 2021), and now trades below US$3.[14] Rocket Internet and MTN have both since divested their holdings the company has faced a barrage of questions from members of the media and public at large. They have had to defend their claims of being an African firm and counter accusations of fraud. Jumia has never turned a profit. In 2022 it reported losing as much as US$227m.[15] To put the firm back on a path to profitability a new management was brought in. Operations in four of its 14 markets were wound up[16] and 20% (900 people) of its workforce was laid off.[17]

Operational and management issues aside, Africa is a difficult place to do business. Jumia’s 2019 annual report shows that the company’s fulfilment expenses (cost to ship and deliver orders) were US$1.6m higher than its gross profit. Managing logistics in Africa is particularly challenging. Informal spatial and suburban planning in many areas make precise delivery addresses difficult to identify. That can result in failed deliveries, order cancellations and returns, which for Jumia, are as high at 20%. The remoteness of some delivery areas as well as underdeveloped road infrastructure have meant that the company has had to adapt its delivery methods, which include bicycles, roller-skates, and more recently, drones.[18] This creates additional layers of complexity and adds costs to what is already an expensive business model that works on thin margins.

While Jumia’s balance sheet remains relatively free of debt it has only US$228m in cash reserves left. At its current burn rate Jumia may have only a year worth of runway before having to raise debt or issue shares, neither of which is likely to be well received by investors.

Online retailers are cash hungry, requiring enormous scale before becoming profitable. South Africa’s Takealot is another example of an African e-commerce leader yet to make a profit.

Takealot – South Africa

Takealot was officially launched in 2011 after US based investment firm, Tiger Global Management[19] acquired and rebranded Take2, a South African e-commerce player founded in 2002.[20] In 2014, the company merged its operations with Naspers-owned Kalahari.com, which at the time, was a market leader in online sales of games, books, music, DVDs, cameras, and electronics in South Africa.

In the announcement of their merger, Takealot acknowledged that without scale “SA retailers simply can’t compete successfully against the local brick and mortar retailers and foreign companies such as Amazon and Alibaba.[21]” At the time, both Kalahari and Takealot were loss-making.[22] To add greater scale and logistics capabilities to the business, Naspers completed a full buyout of Takealot in 2018 grouping it with online clothing retailer, Superbalist and Food Delivery business, Mr D Food.

Despite accounting for half of South Africa’s online purchases, Takealot incurred a US$13m trading loss in the six months to June 2022 on sales of US$384m. Like Jumia, rising logistical costs and complexity are one of the reasons the company has yet to turn a corner. A weaker exchange rate, higher inflation, rising interest rates and pressure on disposable income have been a blow to both sales and operating expenses.

The group’s latest loss comes at a time when Amazon is readying to enter the South African market, and brick and mortar retailers are fighting back with their own delivery platforms. The country’s biggest retailers, Checkers (Sixy60), Woolworths (Woolies Dash), Pick ‘n Pay (PnP Express), Makro / Walmart and Mr Price among many others have all launched e-commerce platforms that leverage their existing store infrastructure across the country, allowing same-day delivery. To compete, Takealot has had to invest substantially in additional warehousing, inventory, and distribution centres, pushing out its breakeven timeframe.

Nevertheless, the runway for Takealot is decidedly longer. Despite multiple cash injections of hundreds of millions of dollars, Takealot’s parent firm, Naspers, has deep pockets and is intent on staying the course.[23]

Kilimall – Kenya

Nairobi based Kilimall has styled itself as a marketplace rather than a true e-commerce retailer. It is a relatively new entrant to Africa’s e-commerce space, having launched in 2014. It is the second biggest e-commerce platform in Kenya after Jumia and was founded by ex-Huawei employee Yang Tao who started the firm in response to his frustration at the limited range and high cost of goods in Kenya. Kilimall is for all intents and purposes is a Chinese company that was started in Kenya to offer small businesses a way to sell their products to Kenya’s growing digital shopping market. It has since grown to over 10,000 sellers from both Africa and China[24], and exports Kenyan products to Chinese buyers. The e-commerce platform also offers an online payment system, Lipapay, and logistics system KillExpress. The firm’s strong connection with the world’s biggest manufacturing hub are seen as a distinct competitive advantage. While a great deal less is known about Kilimall, its ownership structure and trading performance (purportedly as high as US$72m in sales annually[25]), the company has faced a wave of complaints about the poor customer service, quality of its products or orders not being delivered at all.

Kilimall’s expansion into Uganda and Nigeria was short-lived. Barely two years after launching in Kampala in 2016 it decided to exit. Talks with private investors to sell out the Ugandan unit collapsed, leaving rival Jumia with an 80%[26] market share in the country.[27] Ironically, months before exiting Uganda, founder and CEO announced plans to be present in all African countries by 2022.[28]Kilimall’s Nigerian domain too, has been shuttered.

The experiences of Jumia, Takealot and Kilimall highlight the challenges faced by e-commerce players in Africa, but also the industry more broadly. They also suggest that the excitement around e-commerce in Africa belies the difficult trading conditions on the continent and lack of profitability. There is a multitude of challenges to navigate just to complete a sale, let alone fulfil the order and make a profit in the process.

Internet connectivity and the cost of data

Poor internet connectivity and the high cost of data are less of an issue than they have been in the past but are nevertheless an inhibitor to faster and broader adoption of mobile browsing and conversion to sale. While data costs have eased over the past 5 years, Africans still spend a disproportionately high amount of their average monthly income on connectivity (figure 6).

E-commerce sites in Africa (as with the rest of the world) have been optimised for mobile browsing and low data consumption but true progress will only be achieved through regulatory reform that force data costs lower and the wider roll-out of free wi-fi in public areas.

In South Africa, mobile telecommunications providers have lowered exorbitant data costs under pressure from government and the public, even “zero-rating” certain government, educational and employment websites, where browsing does not use the customers data. Instead, zero-rated sites are effectively subsidised and paid for by the zero-rated site owners.[30] Considering how few e-commerce platforms in Africa are profitable, it is difficult to see how they would be able to carry the cost of zero-rating, and whether the cost would be more than offset by sale conversions. Nevertheless, e-commerce platforms will have to become more creative in attracting and converting site visits in a data-constrained environment.

Payments and the trust deficit

Given Africa’s large unbanked population, many consumers either operate on a cash basis (often outside the formal economy) or rely on mobile money and digital wallets. At just 31.5%, Africa has the lowest proportion of adults with a bank account anywhere in the world. The continent does, however, have the highest proportion of its adult population with a mobile money account globally (22.5%) (figure 7).